COLIN STOKES:

Hi Professor Fan! Thank you for meeting to speak about your work. Would you talk a

bit about your current work, and the projects you're most excited about right now.

PROFESSOR RANRAN FAN:

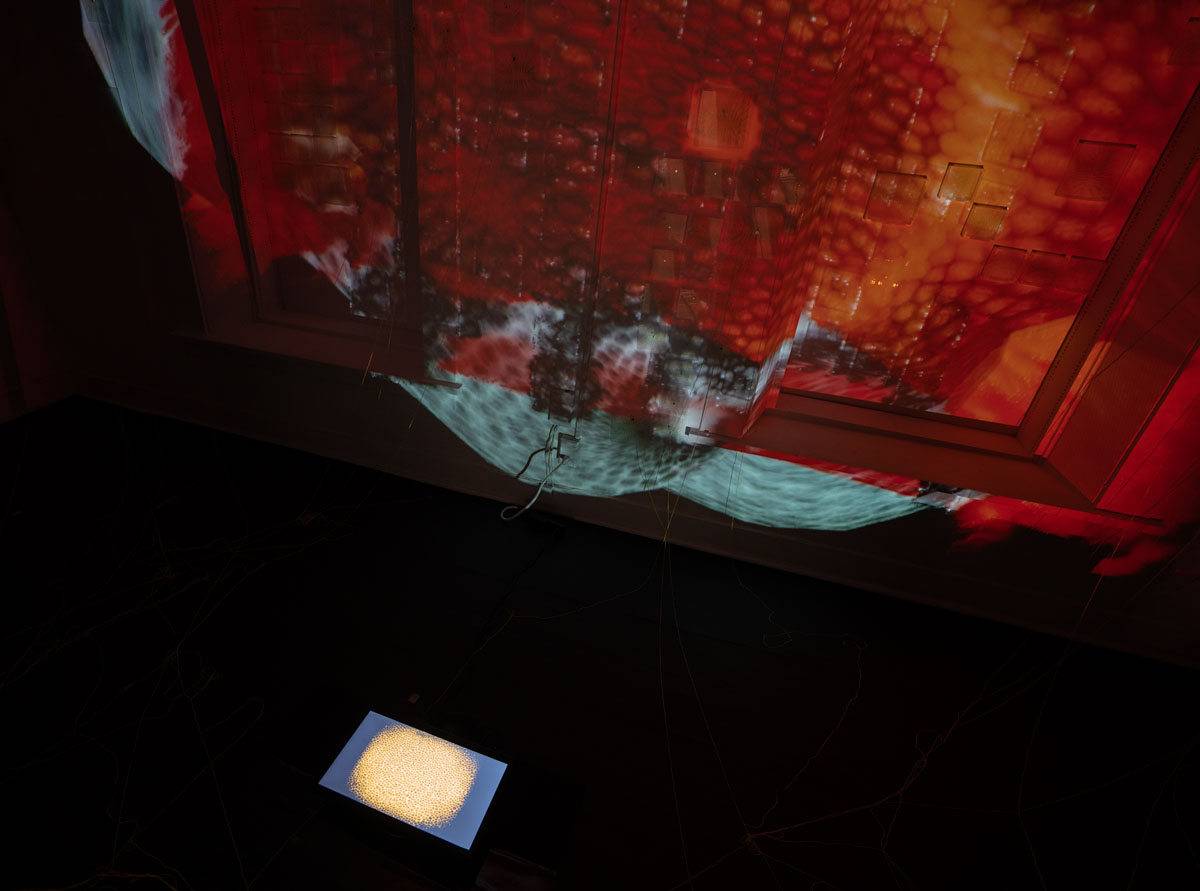

Hi Colin! I have a solo show coming up in Austin in March 2025. For this project,

I’m building and training several AI models. The installation will be immersive, almost

like a giant machine that functions as a clock. However, it’s less about keeping time

and more about exploring how we perceive it. The clock, moderated by AI, will allow

audience participation—they can input information, and the AI will respond based on

what they provide. It’s a dynamic interaction between the AI and the audience.

It’s a project working on the idea of an unreliable timekeeper or a modifiable timekeeper. It’s addressing experiences with PTSD, like when you are triggered by something and you’re stuck in a panic-attack mode. You feel like you're stuck in that time, that moment, and you can’t really get out. The timekeeper is a way of maybe changing how people perceive time, so there would be an exit, where you can get out of that moment, and your body can start moving again, and your mind can get over that really frozen mode.

CS: Incredible. Can you tell me a little more about the AI component of this? We’re so focused on it over here in the Composition department. What types of models are you using, and how are you training them?

RF: So now I’m thinking because there are different types of AI models. Some are very basic—it’s basically going to present itself as a chatbot. There are different types of chatbots. Some involve deep learning, like ChatGPT, generating a lot of things by itself—it depends on how you train them and your input. What I’m focusing on is actually the one that’s less “intelligent,” you could say. It analyzes the information you input, so it guesses the topic of what you're talking about, the sentiment of your messages, and it responds. I will connect that with a large sculpture I’m also creating, which moves like a robot, so the analysis from this AI will trigger the robot’s actions.

So, there’s some sentiment analysis as well. I’m really interested in using sentiment analysis for these multi-modal designs where you have maybe a language model on the front, and you can process the emotion of the input text and then use that information to direct certain actions. There are public concerns about AI, which might come from fear. But I want to use this work as a way for people to learn more about how AI is constructed. If you fear something, it's often because you don’t know it. But if you get more information, maybe you’ll feel more comfortable working with it.

CS: Interesting! I know some people who say things like, “AI should be banned,” but they love their apps that identify bird calls or plants in nature using AI, right?

RF: Yeah, we actually use AI all the time, like with all the chatbots. When you Google something or search, it’s all AI.

CS: Let’s pivot here for a moment, because I’m curious what drew you to New Media and installation art as your primary modes of expression? If I’m even characterizing that correctly… please correct me if I’m not!

RF: So my background is actually in science before art, and I didn’t even get into art until my final year in college. For me, I see every medium as just that—a medium. I prefer not to categorize them. Even though we say, "This is art, this is science, this is economy," I see them as different mediums. So, with New Media, I’m more drawn to the “new” aspect rather than the technology itself. I use emerging technology, but I also use unconventional mediums in traditional art, like participatory performance, scent, and even food. For example, I’m an incense maker, and I make incense from scratch. These are all part of New Media for me because I see them as ways to communicate in new ways with people.

CS: You’re really thinking multi-sensorially. It’s funny how we often limit ourselves to just sight and sound, but touch, scent, and even temperature are also key parts of how we experience the world.

RF: Exactly. We’re limited by what our bodies can sense, and there’s a lot more out there to explore.

CS: That’s fascinating. Thank you! Do you have any other artists or movements that have influenced your work or that you find especially interesting?

RF: I draw inspiration from many sources—philosophers, scientists, and recently, history too. One thing I’ve been reading about is astrology. I’m currently reading a book about Archeoastronomy, which looks at how people thousands of years ago studied astrology to understand time. Because I’m from China, I’m also interested in how the Chinese understood time, measured it, and determined locations based on it. All of that is giving me a lot of inspiration for my work, especially with my current project around timekeeping.

CS: We touched on this a little earlier, but how do you see the line between New Media and other forms of contemporary art? Is this line meaningful? And what role does New Media play in the larger conversation around contemporary art?

RF: I think it really depends on where we stand. If we were living a hundred years ago, photography would have been considered New Media because it was the emerging technology of that time. If we go back a couple of hundred years, painting might have been the New Media. So, it depends on our current perspective. I always see New Media as addressing and developing the technology or medium of the moment. All forms of technology or medium were considered New Media in the past.

CS: Yeah, that really makes sense. It’s like New Media is the incubator for whatever new technology or form emerges. That’s a really nice perspective.

RF: Exactly. And as time goes on, what we now consider New Media will become part of the canon, just like the technologies of the past.

CS: So, getting back to AI: How do you see AI transforming the landscape of New Media and digital art?

RF: That’s a really good question, but I don’t think I can fully answer it yet. AI is so new, and we’re still trying to understand how it works and how to integrate it into our practices. For now, I see it as assisting and facilitating processes. One of the challenges in the future will be around copyright and authorship in the art world. AI can generate images, sounds, and music, but it’s still based on the training data you feed it. At some point, society will likely develop a consensus on how AI can be used in creative fields, but by the time that happens, new technologies will emerge, and we’ll be playing catch-up again.

CS: Yes, that seems inevitable.

RF: I think it’s better to move away from a human-centered perspective. If we stop viewing ourselves as the center of everything, AI can be seen as something that just exists, like plants or animals. AI doesn’t need to be something we dominate or control. It reflects our humanity and the way we treat it could be respectful, like how we should treat different species.

CS: That’s a fascinating perspective. I’ve never heard it framed that way—AI as an emergent entity, something we learn to coexist with, rather than something to control. It’s really refreshing.

RF: This idea actually comes from a reading I did in a graduate seminar called Making Kin with the Machines. The text discusses indigenous perspectives on relationships with machines, suggesting that we don’t have to dominate AI, but rather we can work with it in a respectful way. It’s still new, and we don’t know if it’s practical yet, but it’s an exciting thought.

CS: Very interesting. I love that. Well, it’s definitely exciting to be at the front edge of something so new and not-yet-understood. It feels like the first time in my life I’ve been on the edge of something in this way—it’s exciting to be part of something we don’t quite know how to handle yet.

RF: Exactly! It’s very similar to Daoism in Chinese culture, where human life is seen as just one part of the whole system. Things just happen, and we have to figure out how to work with them. I think that’s what drives me to think from a non-human-centered perspective.

CS: That’s fascinating, thank you RF. As an add-on to this discussion, how do you see the ethical issues surrounding AI? We touched on the copyright issue earlier, but beyond that—especially in visual media, where people can ask an AI implementation to create something remarkably similar to a Kandinsky or other famous works—how do you see the ethical implications of AI?

RF: To be honest, I’m not too worried. I don’t think AI can generate truly creative work. AI is limited by its training data, so it’s bound by what already exists. One of the most powerful aspects of human creation is the ability to create something entirely new—something that’s never existed before. Even if people say there’s nothing new under the sun, I still believe in human innovation. AI is restricted in that way. And what’s more important, as time passes, people will likely crave human-made things because, as humans, our communication and connection are essential. No machine can replace that.

Ranran Fan is an Assistant Professor in Studio Art, New Media at University of North Texas.

Ranran Fan is an Assistant Professor in Studio Art, New Media at University of North Texas.

She is a device-maker and an artist who works in installation, new media and performance. Fan has presented immersive installations in solo exhibitions in Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Salem, Oregon, The Print Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Currents 826, Santa Fe, New Mexico, No Land, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Sanitary Tortilla Factory, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Fan's work has also been included in group exhibitions internationally such as Academy Art Museum, SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe Art Institute, Tamarind Institute, OCT Contemporary Art Terminal, China, and Incheon Marine Asia Photography and Video Festival, Korea.

To find out more about Prof. Fan's works, visit https://ranranfan.com/.